Passive Stretching is Not the Devil

Passive Stretching is Not the Devil

Passive stretching has gotten a bad rap y’all.

While there has been a lot of research to support that just passive stretching isn’t a great way to increase your flexibility, and most people make more, faster, progress by including drills that focus on their active flexibility - that doesn’t mean you should stop doing passive stretches!

Recommended Related Post: What is “Active Flexibility” and Why is It So Important? — Dani Winks Flexibility

YES, active flexibility training is hugely important for many students. And most* students will probably benefit from having the majority of their training focused on strengthen-while-you-stretch type drills.

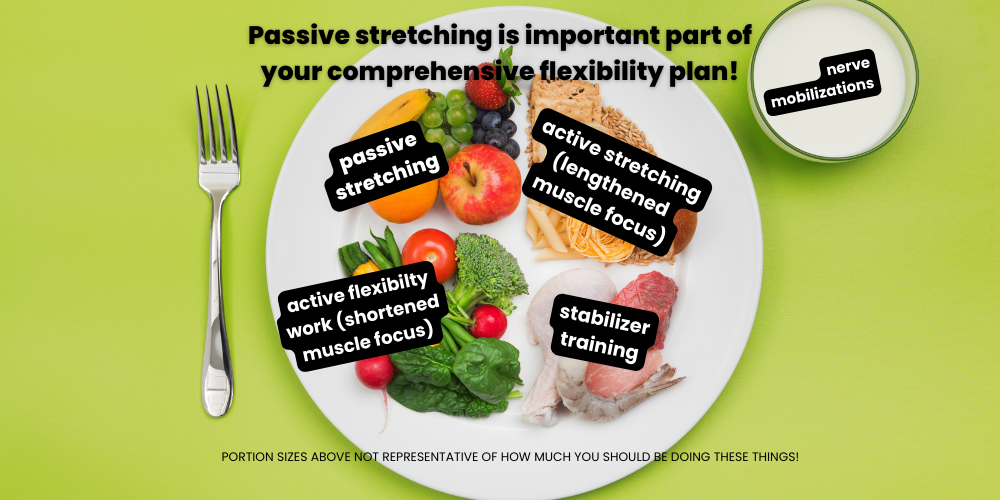

But active flexibility drills are only PART of a well-rounded training routine.

At the bare minimum, your flexibility training routine should consist of a mix of:

passive stretches

active stretches that focus on strengthening the lengthened muscle(s)

active stretches that focus on strengthening the shortened muscle(s)

drills that engage and strengthen the smaller stabilizer muscles (in a position similar to your target stretch)

nerve mobilizations (if you have nerve tension)

How much of each type of these drills you choose will depend on your unique body situation (this is where working with a coach to help guide you can be a big help!).

What Is Passive Stretching Good For?

Even before getting into the fancy “science-y” reasons of why passive stretching is beneficial, one reason I like to include passive stretching in my classes (and in my own training!) is because it is a great opportunity to practice “proper” form/alignment in a stretch before turning it into an active stretch. Say you want to do an active drill for your hip flexor flexibility, like lunge knee taps or hip flexor contract-relax in a lunge. Start off with a regular ol’ passive lunge, and while you’re in the passive stretch, run through your mental checklist of “proper” hip position in a lunge to ensure they’re not cheating the stretch. If you can’t hold a passive lunge with good form, there’s no way in heck you’re going to be able to when you try to make it more active (which would defeat the purpose of then trying to strengthen that position…).

Now the more science-y explanation is that longer hold passive stretching helps our Central Nervous System (CNS) get more comfortable with allowing our muscles to lengthen farther, it essentially helps us temporarily increase our stretch/pain tolerance. When we lengthen our muscles in a stretch, the “stretch reflex” kicks in, which is our nervous system telling the muscles to contract and resist further lengthening because it perceives the position as unsafe. Continuing to hold the passive stretch, and breathing slowly, can give the nervous system time to recognize “oh hey, this actually isn’t so bad, maybe we can let this muscle go a little bit longer after all” (up to a point, of course this has it’s limits!). If you want to nerd out in more detail, Dan Van Zandt has a great blog post that cites a ton of research on different potential mechanisms on how static passive stretching accomplishes this (he also has an amazing Instagram if you’re looking for more bite-sized research-based flexibility tips!).

So we can use passive stretching to help our body get comfortable going into a deeper range of motion, and then use active drills to strengthen that new, deeper range of motion!

Said a different way, our active flexibility will always be limited by our passive flexibility. Let’s look at a middle split and a straddle as an example. A middle split is a passive stretch, with gravity doing the work of pushing your legs wider into the floor. A seated straddle, on the other hand, can be an active stretch, where you need to use your glutes to actively pull your legs out wide. So if you have a very far-from-flat middle split, your straddle is going to be pretty narrow as well. So for folks who’s goal is a wider seated straddle, working on their middle splits before doing more active flexibility drills for their adductors (inner thighs) can be super helpful!

A Practical Example: Active ROM Before-and-After Passive Stretching

Let’s take a look at a what a difference some passive stretching can do in a standing split. In a standing split, the bottom leg is in a mostly passive hamstring stretch (one could argue the hip flexors could be contracting to tilt the pelvis and deepen the forward fold, but realistically I do a lot of pulling with my arms), and the top leg is in an active hip flexor stretch (the glutes and hamstrings are contracting to pull the top leg backwards, stretching the hip flexors in the front of the hip).

I took the photo on the left after just doing a basic warm up (remember, I’m a contortionist so I have worked hard to be able to get this range of motion mostly cold!). I can get my legs preeeeeetty close to flat, but it’s really the tight hip flexors in the top leg that are preventing me from being able getting my split flat.

Then I did about 3 minutes of passive stretches (standing split into the wall, the “couch stretch,” and a regular ol’ kneeling lunge).

Then I took the photo on the right, where you can see both my (passive) hamstring flexibility in the bottom leg has improved (I’m in a slightly deeper forward fold), AND the active hip flexor flexibility in the top leg has improved as well!

So now that I’ve gotten my body to be able to find my deepest range of motion with passive stretching, I can do active drills (like standing split kicks) to strengthen that range of motion.

Here’s what that would look like with and without the passive stretching. If I just tried to do my standing split kicks (and active flexibility drill) without passive stretching, you can see how I can only kick just shy of my split. BUT after doing a bit of passive stretching and getting that deeper split position, now I can go deeper into my active stretches, strengthening my muscles to support this even deeper range of motion:

Too Much of a Good Thing

It is important to note that passive stretching can absolutely be overused. Like I mentioned earlier, most* students need to train more active flexibility than passive flexibility to see improvements. For many students, spending a ton of time doing passive stretches to increase their passive flexibility is at best, a waste of time, and at worst, a recipe for injury.

Passive flexibility is, as the name suggests, passive (an outside force is applying the force to stretch the joint), which can lead to instability in the joint. Hypermobile students (folks who already have looser connective tissue in their joints that reduce stability) are at even more risk for overstretching their joints with noodle-y passive stretches.

Generally, we want to strive to train our active flexibility to come closer to our passive flexibility to reduce the risk of injury. Kristina Nekyia of Fit&Bendy fame has a great blog post on this if you want to read more.

So How Much Passive Stretching Should You Do?

Just like virtually every question related to flexibility… it depends! Depending on your unique body situation, you may benefit from peppering in more passive stretching into your training routine, or you may be better cutting out some of the passive stretches and replacing them with active drills.

GENERALLY speaking (take these with a liberal pinch of salt):

Consider including more emphasis on passive stretching if…

You are new to stretching

You feel like your muscles are super tight and won’t budge

Your active range of motion and your passive range of motion are already quite similar

Consider including more active stretching if…

You have a large difference between your passive ROM and your active ROM

You are hypermobile

You need an active ROM for a particular skill

Personally, as a contortionist, I’d estimate that my training (across shoulders/back/hips/etc) breaks down into about 85% active stretching, and 15% passive stretching. I use passive stretches targeting at specific areas that I know need a little extra coaxing to open up (hello hip flexors!) early on in my training routine, as well as pepper them in throughout to use as mini “stretch breaks” to give my body a rest between active drills.

If you want more tailored advice on how much passive vs. active stretching YOU should be doing to meet your flexibility goals, that’s where working with a flexibility coach who can assess your current flexibility and strength can be a great way to get some expert guidance!

* Note: Some students are able to make quite a bit of flexibility progress from passive stretching alone, and there have been studies where subjects have made flexibility improvement just with passive stretching. But when it comes to what works best for the majority of people, taking a more comprehensive approach where you include strengthening is going to be a safer, and likely more effective (aka GET THOSE GAINZ) approach.